(I’m grateful to Jerome for writing this review since I am being quite lazy about writing. Jerome Kuseh is a “Ghanaian who mostly blogs about politics and business. He is also a fan of literature and has sometimes written poetry. His business blog is ceditalk.com and for his posts about politics, social issues and his attempts at creative writing, visit readjerome.blogspot.com.”)

Intro

After failing to participate in both 2012 and 2013, I decided to take part in his year’s Africa Reading Challenge. This March has been reserved for books by African women authors only, to make up for my deficiency in that regard. I have just read Buchi Emecheta’s Second-Class Citizen and I’m halfway through Bessie Head’s When Rain Clouds Gather. Not being a book blogger myself, I have taken up Kinna’s opportunity to share my review of Second-Class Citizen on her blog. I would like to thank her for the opportunity and for getting me to explore African Literature after I had spent the better part of 2013 reading European classics.

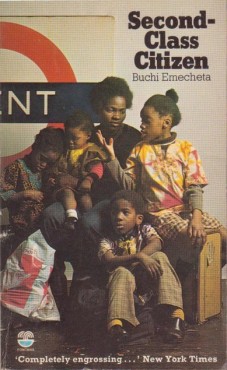

Second-Class Citizen by Buchi Emecheta

It had all begun like a dream. You know, that sort of dream which seems to have originated from nowhere, yet one was always aware of its existence. One could feel it, one could be directed by it; unconsciously at first, until it became a reality, a Presence.

So began the story of an Igbo girl from Ibuza, who was born and raised in Lagos. A young girl named Adah who did not know her age because her parents had not seen the need to record the date, seeing as she was a girl when they had wanted a boy. So she guessed her age as eight, and was certain she was born during World War II.

The “Presence” described in the opening passage was her determination to go to the United Kingdom, a dream inspired by the adoration given to an Ibuza native who had just returned from the UK after earning a qualification as a lawyer. The “Presence” was so strong that it drove her to find her way to school on her own, against her mother’s wishes and even after her supportive father’s death. The “Presence” drove her to earn a scholarship to Methodist Girl’s school, to marry a man, Francis, in order to have a home for her studies (since a woman living alone would be regarded as a prostitute), to earn a high-paying job at the US Consulate and to pay for her husband’s trip to the UK to chase his elusive dream of qualifying as an accountant to pave the way for her dream to be fulfilled. One cold morning, after a long sea journey with her two children, the quest of the “Presence” had been fulfilled.

She had arrived in the United Kingdom. Pa, I’m in the United Kingdom, her heart sang to her dead father.

One would think that the iron will of this young Igbo girl who overcame all hurdles to achieve her dreams would be enough for one story. However, the UK (England specifically) was not what Adah had hoped it would be. Perhaps, she should have been warned by the cold that greeted her. England was cold in every possible way.

As her husband explained to her, she was a second-class citizen there because she was black. That means she had to give up her class privilege (that she had worked hard to earn) and accept the same jobs people with the education of her maids back home would do. Perhaps, if Adah had just accepted this role that had been carved for her, the story would’ve been simpler. But she was who she was, and she had to go get a job at a library and refuse to let her children be taken to foster homes. She was trying to live like a white person. She had broken the unwritten laws of her Nigerian neighbours and irked the childless landlady, so they were thrown out of their meagre apartment and had to rent a room in the house of an old Nigerian man and his white wife.

Now her husband, Francis, felt entitled to all the privileges of an Igbo man over his wife, while not feeling obliged to undertake any responsibility whatsoever. He cheated on her, he beat her, refused contraception on the basis of Roman Catholicism and refused to work on the basis that as a Jehovah Witness, the world was transient and that he had to only focus on the kingdom of God in the afterlife. So he fed fat on his wife’s wages, making no effort to study properly even though he had no work and kept failing his Cost and Works accounting examinations. In time, he became jealous of his wife’s achievements and was determined to thwart all her efforts.

What I find intriguing about Second-Class Citizen is the way in which Emecheta questions religion without drawing any conclusion – from the question of Jesus’s status as son of God to whether it was man’s rib that a woman was fashioned out of. Adah continuously sees the hypocrisy of her husband’s religion and yet in many parts of the book she had turned to God in distress. God had become a personal helper as opposed to the head of an organised religion.

Another intriguing phenomenon is how much Adah wishes her husband would love her and treat her kindly and how hard she worked to save her marriage. Reading the book, there were times when I was outraged and wished I could speak to Adah to get her children and leave the useless man. Her desire for nothing more than love and appreciation of her extraordinary efforts from her husband is just like Mara in Amma Darko’s classic Beyond the Horizon.

From reading the book, one also comes across the tensions between the Igbo and Yoruba people of Nigeria. I recently read Chinua Achebe’s There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra and this book mirrors the levels of distrust between the two major ethnic groups of Southern Nigeria, that is exhibited even in the United Kingdom.

I am in no doubt that Second-Class Citizen is largely based on Buchi Emecheta’s on life. Like Adah, she also went to the UK from Nigeria, left her husband with her children, and became a writer. I have recently acquired her autobiography, Head Above Water and I am anxious to see if there are similarities to the events of Second-Class Citizen. In further proof of my new-found admiration for Emecheta, I have bought, arguably, her most famous work The Joys of Motherhood.

Second-Class Citizen is a great start to my month of reading African women writers, however it should not be kept in such a narrow context. It is raises philosophical questions that transcend the African context. It would make a great read for anyone from any background and I highly recommend it.

[…] is Jerome Kuseh’s third review for Kinna Reads; his previous reviews are Buchi Emecheta’s Second-Class Citizen and Bessie Head’s When Rain Clouds Gather. Jerome is a “Ghanaian who mostly blogs about […]

LikeLike

[…] is Jerome Kuseh’s second review for Kinna Reads; his first was on Buchi Emecheta’s Second-Class Citizen. Jerome is a “Ghanaian who mostly blogs about politics and business. He is also a fan of […]

LikeLike

[…] (I’m grateful to Jerome for writing this review since I am being quite lazy about writing. Jerome Kuseh is a “Ghanaian who mostly blogs about politics and business. He is also a fan of literature and has sometimes written poetry. […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on speakghana.

LikeLike

The Story sounds exactly like a true life story that I know.

I’ve never understood the man.

Would find time to get the book

LikeLike

Thanks, Jerome, for the review. I’m hoping that you will continue reading African women writers even after the month of March. I haven’t read Second-Class Citizen. I’m very familiar with The Joys of of Motherhood which is really really good. I see your mention of Darko’s Beyond the Horizon though I gather that Adah didn’t start from a similar background like Mara’s. I wonder too if it mirrors Emecheta’s life.

As I’ve said, you are welcome to repeat this act anytime!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kinna. I will certainly read more African women authors after March; the collection I’ve gathered cannot be finished this month.

LikeLike